In the Renaissance period Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) in his famous The Notebooks in Note 946 “Refutation of the Pliny’s theory of the saltness of the sea” polemicize with Pliny: “Pliny says, that the water of the sea is salt because the heat of the sun dries up the moisture and drinks it up; and this gives to the wide stretching sea the savour of salt. But this cannot be admitted, because if the saltness of the sea were caused by the heat of the sun, there can be no doubt that lakes, pools and marshes would be so much the more salt, as their waters have less motion and are of less depth; but experience shows us, on the contrary, that these lakes have their waters quite free from salt. Again it is stated by Pliny that this saltness might originate, because all the sweet and subtle portions which the heat attracts easily being taken away, the more bitter and coarser part will remain, and thus the water on the surface is fresher than at the bottom; but this is contradicted by the same reason given above. Again, it has been said that the saltness of the sea is the sweat of the earth; to this it may be answered that all the springs of water which penetrate through the earth, would then be salt. But the conclusion is, that the saltness of the sea must proceed from the many springs of water which, as they penetrate into the earth, find mines of salt and these they dissolve in part, and carry with them to the ocean and the other seas, whence the clouds, the begetters of rivers, never carry it up. And the sea would be salter in our times than ever it was at any time; and if the adversary were to say that in infinite time the sea would dry up or congeal into salt, to this I answer that this salt is restored to the earth by the setting free of that part of the earth which rises out of the sea with the salt it has acquired, and the rivers return it to the earth under the sea.”

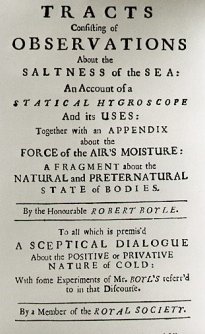

Scientific work on ocean salts was first done by the celebrated British natural philosopher Robert Boyle in 1674 with his publication of “Observations and Experiments in the Saltness of the Sea” :

“The Cause of the Saltness of the Sea appears by Aristotle’s Writings to have busied the Curiosity of Naturalists before his time; since which, his Authority, perhaps much more than his Reasons, did for divers Ages make the Schools and the generality of Naturalists of his Opinion, till towards the end of the last Century, and the beginning of ours, some Learned Men took the boldness to question the common Opinion; since when the Controversie has been kept on foot, and, for ought I know, will be so, as long as `tis argued on both sides but by Dialectical Arguments, which may be probable on both sides, but are not convincing on either. Wherefore I shall here briefly deliver some particulars about the Saltness of the Sea, obtained by my own trials, where I was able; and where I was not, by the best Relations I could procure, especially from Navigators.”

After all, (says he,) it may be observed, that we are inquiring into the cause of a phenomenon, which it may be said had no secondary cause at all. It is taken for granted, in this disquisition, that the water which covered the globe in its chaotic state, was not impregnated with salt as at present, but quite fresh: now this is an opinion concerning a matter of fact, which can never be proved either way; and surely we extend our speculations very far, when we attempt to explain a phenomenon, primeval to, or coeval with, the formation of the earth.”

This sensible writer then states the different experiments which have been made to discover the saltness of the sea, round the shores of Britain; and proposes the following simple method of ascertaining it with tolerable certainty:”As it is not every person who can make himself expert in the use of common means of estimating the quantity of salt has g contained in sea water, I will mention a method of doing it, which is so easy and simple, that every common sailor may understand and practise it; and which, at the same time, from the trials I have made of it, seems to be as exact a method as any that has yet been thought of. – Take a clean towel, or any other piece of cloth; dry it well before the sun or before the fire, then weigh it accurately, and note down its weight; dip it in the sea water, and, when taken out, wring it a little till it will not drip when hung up to dry; weigh it in this wet state, then dry it in the sun or at the fire, and when it is perfectly dry, weigh it again: the excess of the weight of the wetted cloth above its original weight, is the weight of the sea water imbibed by the cloth; and the excess of the weight of the cloth after being dried, above its original weight, is the specific gravity of the salt retained by the cloth; and by comparing this weight with the weight of the sea water imbibed by the cloth, we obtain the proportion of salt contained in that species of sea water.” Whoever undertakes to ascertain the quantity of salt contained in sea water, either by this or any other method, would do well to observe the state of the weather preceding the time when the sea water is taken out of the sea; for the quantity of salt contained in the water near the surface, may be influenced, both by the antecedent moisture, and the antecedent heat of the atmosphere. And this leads to the consideration of a question proposed by Aristotle, – Why are the upper parts of the sea Salter and warmer than the lower? Some philosophers, admitting the fact, have followed him in attempting to explain it; whilst others have thought themselves authorized by experiment to deny the truth of the position; and those, perhaps, will argue with the greatest justness, who shall affirm that it is neither generally to be admitted, nor generally to be rejected, but that the sea in some places, and under certain circumstances, is salter and warmer at the surface, than at any considerable depth beneath it, while in many others the reverse is true. The question consists of two parts, betwixt which, though there probably is a connection, yet it is not so necessary a one as to hinder us from considering each part by itself.With regard to the use of this salt property of sea water, it is observed, that the saltness of the sea preserves its waters pure and sweet, which otherwise would corrupt, and emit a stench like a filthy lake, and consequently that none of the myriads of creatures which now live therein could exist. From thence also the sea water becomes much heavier, and therefore ships of greater size and burden are safely borne thereon. Salt water also does not freeze so soon as fresh water, hence the seas are more free for navigation.

Boyle measured and compiled a considerable set of data for variations in the saltness of surface seawater. He personally made a series of observations on the water of the English Channel, collecting it from various depth, and observing its specific gravity. He also designed an improved piece of equipment for sampling seawater at depth, but the depths at which it was used were modest: 30 m with his own instrument, 80 m with another, similar sampler. Boyle investigated the saltness of the water by a number of processes: he tried the estimation of total solids by direct evaporation and ignition, but not being satisfied with result, he ultimately took the density as an index of the saltness, and determined this either by means of a glass hydrometer, by weighting in a phial which was afterward weighted when full of distilled water, or by weighting a piece os sulphyr in distilled water and sea water consecutively.His measurements of the salt in seawater were done also by precipitating the salt. He recommended the use of silver nitrate to determine the sweetness of all waters (Boyle, 1693). For the next century, no systematic studies of sea water salts were done using a common analytic scheme.

Visit Today : 83

Visit Today : 83 Visit Yesterday : 331

Visit Yesterday : 331 This Month : 1046

This Month : 1046 Total Visit : 321040

Total Visit : 321040 Hits Today : 89

Hits Today : 89 Total Hits : 741598

Total Hits : 741598 Who's Online : 1

Who's Online : 1